With the summer travel season nearly upon us, we are put in mind of the inevitable waiting involved. Waiting in airports. Waiting on family members. Waiting in line for amusement rides.

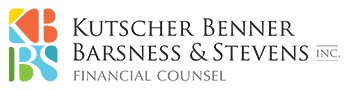

Federal Reserve Chair Powell’s press conference following the most recent Fed meeting had the same feeling as when the airport gate attendant finally announces the official delay that expectant travelers milling about had already sensed: the scheduled departure will be delayed, further announcements to follow as information becomes available. The last three monthly readings on inflation were higher than expected and may indicate some kind of plateau; therefore, the Fed moved out expectations for the first cut of interest rates to toward the back half of 2024, delaying the ultimate action that was previewed by Powell at his December press conference. The perceived “pivot” in Powell’s message toward the first cut kicked off this strong run for stocks that can be seen in results below for the first quarter of 2024.

The big difference, of course, is that at airports everyone is trying to get someplace and is inconvenienced by delay. Financial markets, on the other hand, are a jumble of participants with all manner of interests and objectives competing with each other. The apparent yawn that greeted Powell’s May announcement indicated investor satisfaction with the state of the economy and agreement with the Fed that the relatively small and contained pockets of economic stress aren’t worrisome enough to warrant stimulative action (cutting rates) in the face of stubborn inflation readings.

In this letter, we check in on how several themes we’re monitoring are evolving and what to make of the terrific results for stocks and struggle for most bonds during the first quarter.

In general, the US economy is tolerating higher interest rates pretty well. Consumer spending and job growth have remained strong and above expectations even as the number of job openings and wage growth are moving down from high levels. Corporate borrowers aren’t suffering much, as most have longer-term debt still at low interest rates; that effect will eventually wear off, but it will take a few years. Corporations are investing in their businesses at higher levels. Indeed, Goldman Sachs estimated before year start that spending on artificial intelligence would add 0.4% to US GDP in 2024. That was an eye-opening projection and seems prescient in light of recent economic strength.

The Prospect for Interest Rates. All this good news begs the question, “Maybe interest rates don’t need to come down much?” As our readers know, interest rates are important for setting the returns from bonds and conditioning expectations for stock prices. Thus, one of the most important considerations for financial markets is where interest rates land when Fed policy is “normalized” following this period of elevated rates that the Fed and most market participants view as temporary, preceding a new longer-term regime to come.

The answer is elusive. What’s normal in the context of dramatic Fed policy since the Global Financial Crisis? We must go back quite some time to consider the historical record. The 10-year US Treasury Note is yielding about 4.5%, and that to us doesn’t look abnormal in the long (100-year) sweep. In the last several months, we have seen opinions proffered by economists and current and past Fed members that the neutral rate of interest, that is, the real rate of interest (the nominal rate minus inflation) that neither cools nor stokes the economy, is rising. Remarkably, there is a long way to go for the conventional wisdom to mark the neutral rate up to anywhere near current interest rate levels. Since the GFC, much of the Fed leadership has estimated the neutral rate at about 0.5% (you may see or hear this rate referred to as “r-star” or “r*” in the financial press). Add 3% for today’s inflation and that suggests the neutral nominal rate is 3.5%, a full 2% less than current rates. Prior to the GFC, the neutral rate was thought to be about 2.0-2.5%.

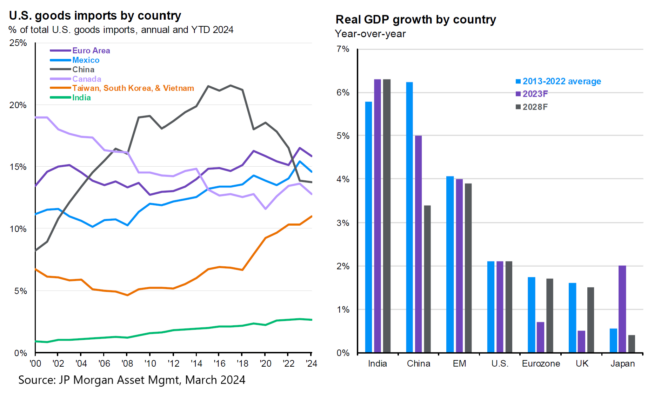

Further, several factors support the view that the rewards for lending need to increase. After the last several years of the US de-industrializing as it relied more and more on trading partners, we are now rebuilding our domestic manufacturing base in recognition, particularly post-COVID, of the drawbacks of relying on adversaries for products and sole sources of supply at a great distance. The US is also in the midst of a massive effort to transition its energy production to renewable sources, and that effort has been made more challenging from the much greater demand for electricity from AI-boosted search engines. Thus, capital is required to build physical assets in the US at a pace not seen in quite some time. With greater demand for that capital, we should expect the price of capital to go up without changes in capital supply.

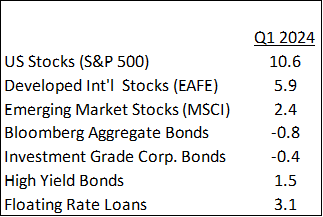

Some of this investment is being financed by federal government programs, contributing to the swelling of the federal budget deficit to an eye-watering 6.5% for the current year. This comes after many years of budget shortfalls at a size larger than the economy grew. Consequently, accumulated federal debt has moved up from about 40% of GDP at the time of the GFC to maybe 110% today (depending on how it is measured). The abundance of US Treasury debt then is both the financial backdrop against which, and the money instrument in which, the pricing of capital is inevitably measured. The greater supply of it looking for an owner adds undeniable upward pressure on US Treasury yields. This major trend informs our judgment that the rewards to lending have improved and are likely to remain favorable overall, and that companies demonstrating diligence in this higher-cost-of capital environment by generating durable positive cash flows deserve greater investment attention than in the more growth-at-any price-focused investment environment of the prior, low-cost-of-capital regime.

Changing Relations among Labor, Government and Business. Besides owners of debt capital, other participants in the economy are government, consumers (or labor) and business owners. It’s useful to check in on them for what recent (or anticipated) changes in the relationship among them hold for stock investors and financial planning issues generally.

–Government, Taxes and Benefits. Government’s take in an economy is a function of taxes. Above we mentioned the growth of government debt. In addition to spending remaining elevated since the GFC and supercharged following the Covid epidemic, tax rates have more or less consistently moved down for the overwhelming majority of US citizens since President George W. Bush cut personal tax rates all across the rate schedule. Most of the action in personal income tax changes since then has been moving the top two rates (currently 35% and 37%) up and down by a couple of percentage points. And in 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 (“TCJA”), cutting the headline corporate income tax significantly in conjunction with attempting to claw back income realized by companies overseas and giving personal taxpayers a much bigger standard deduction while limiting deductibility of state and local taxes and other items.

Thus, one would think that the bias in future tax rates is upward from here. In 2026, for example, the 2017 corporate tax rate, the bigger personal standard deduction, the larger estate tax credit and other changes will sunset and snap back to pre-2017 levels in the absence of Congressional and Presidential agreement for extension or other change. Given the recent performance of Congress, the prospect for agreement would have to be marked down, and the Biden Administration has come out against renewing the corporate tax cut. And, as seen in the chart above, even with the sunset of the TCJA, a significant reckoning of spending and taxes will be required to pare the growth of debt as a share of the economy.

Likewise, we should expect government actors to put pressure on popular entitlements for well-off Americans. It was notable during the Republican presidential primary debates that at least two candidates aired the fairness of limiting Social Security benefits for wealthy citizens. In all likelihood, changes in Social Security to improve its sustainability will involve a variety of levers, including later dates for full retirement, lower inflation adjustments or other benefits for higher income retirees and an increase of the tax base by levying Social Security tax on a higher level of earned income and possibly small business owners.

Thus, we believe it is important to prepare for somewhat higher taxes and less Social Security benefits when working with clients to prepare for retirement. To date, we are not recommending clients cut their projected Social Security benefit across the board, but rather we think for the highest income group future Social Security benefits should not be viewed as a salve that will solve an otherwise unsustainably high level of portfolio withdrawals. With taxes, we think it important to utilize lower taxes today through selective Roth conversions and by not unduly delaying the receipt of income from retirement plans (other than Roth accounts), but instead looking to make withdrawals at a level pace throughout retirement.

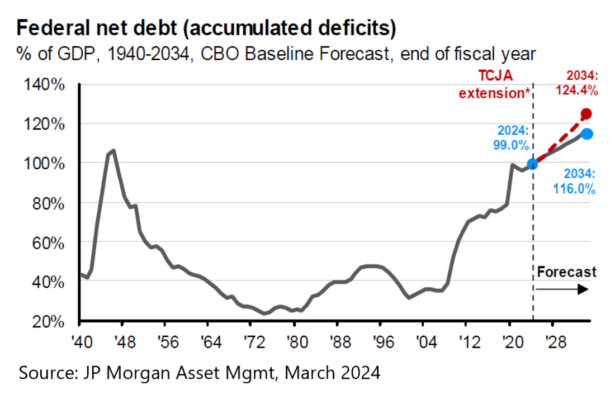

–Labor and Business. The last and largest participants in an economy are workers and business owners. The respective compensation enjoyed by them is a significant driver of the rewards for holding stocks, that is, for being on the business side of this relationship. Above, we mentioned lenders and government and their cut of economic output (i.e., interest and corporate taxes) from business has been low since at least the GFC, creating a tailwind for corporate earnings and hence stocks. Another tailwind for stocks has been the subdued wage gains for workers following the GFC until a couple years before the Covid epidemic, at which point wage gains for the lowest income Americans began to grow more prominently, a trend that has largely continued to this day.

That said, average corporate profit margin (that is, the cents of profit retained by businesses out of every dollar of product sales) swings in long cycles and reverts toward a mean relationship, with the largest driving factor being the cost of labor. Given retirements in the labor force putting pressure on supply and greater union organizing activity (at Starbucks, Amazon, and foreign-owned auto plants), we may be seeing a sustained swing upward in the power of labor to demand better wages. Note also the Federal Trade Commission’s recent attempt to ban covenants-not-to-compete in worker contracts and the general skepticism of the FTC toward corporate mergers that would have been completed without review in an earlier time. An economy less concentrated in a few firms is one where businesses need to compete harder to attract labor.

Thus, with the upward bias on wages, interest and taxes, the share of the economy to be enjoyed by the owners of business would seem under greater pressure, even as the growth of the economy suggests all participants are competing for a share of a bigger pie. This view tempers our expectations for US stock performance as we look out over the next several years.

We are also mindful that over the past 12-18 months, a small number of technology stocks (commonly referred to as the “Magnificent Seven”) have accounted for a dramatically large share of the return in US stocks due to their ability to raise prices and enthusiasm over their involvement in artificial intelligence. Ironically, this concentration buttresses the case for passive index investing since without broad ownership one can miss these winners and the simultaneous desire for diversification through limited active management, focused largely on quality companies, and private equity where appropriate for the client. The latter category is attractive for growth and valuation of the businesses and provides diversification beyond the shrinking number of public companies due to acquisitions and the greater options that substantial private companies have to raise capital and obtain liquidity for owners away from public markets.

World Schism and Reordering of Supply Chains. Last, we revisit our theme of the evolving realignment of nations, which can be characterized as a more defensive posture for the developed democracies as they face autocratic challengers to the world order that prevailed since WWII and especially since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The foremost competitor is China, who is willing to subsidize the export of next-generation high value goods (e.g., electric vehicles and renewable energy components) as it attempts to grow its way out of an immense property bubble and youth unemployment. Chinese export unit volumes are up 10% in the last 12 months even as the value has barely grown, illustrating the deflationary influence of this activity. Europe and the US are responding with tariffs and other restrictions to protect key sectors of their economies.

Meanwhile, India is the fastest growing major economy and continues to attract foreign investment as a substitute for some Chinese capacity. But India remains a non-aligned country (even as its relationship with China sours), and the pathway for democracy and development in Latin America and Africa remains fragile as their autocracies and developed democracies compete for influence. The outlook for the West in this contest is improved with growing acknowledgment in developing countries of drawbacks involved in China’s Belt and Road initiative and “wolf warrior” diplomacy.

Our general view is that this process should be a plus for much of the emerging markets as western firms look to replace sales growth and manufacturing capacity formerly found in China to partners such as Mexico and Vietnam. We also don’t believe all opportunity in China has disappeared. China’s economy isn’t going away, and it has amazing productive capacity, including growing technology in many advanced product areas (e.g., biotech, robots, AI) that the government is promoting. Instead, we have been moving portfolios away from passive ownership of Chinese stocks by changing the relevant index fund to one that excludes China while continuing investments in active fund managers who can use their skill to selectively invest in quality companies within the emerging markets, including China, as they deem appropriate.

* * *

We hope the foregoing review aids understanding of our work on your investment portfolio and financial planning issues. Should you wish to discuss any of the above or have a need to contact us, please do so.

PLEASE SEE IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE INFORMATION AT: KBBSFINANCIAL.COM/NEWSLETTER-DISCLOSURE-INFORMATION/