The turn of the year marks the start of many rituals. In our financial planning practice, we report to clients and their tax accountants about their investment income and expenses in the previous year. And of course, we write letters like this one summarizing the year past in financial markets and giving reflections and observations about the investment environment and implications for clients’ financial health.

This year, we also could spare a thought for college admission officers everywhere, who, facing a pile of applications received over their winter deadlines, now have to decide if application essays are legitimate or the product of some artificial intelligence bot. This special challenge follows in the wake of the November 2022 release of Chat GPT, a “chatbot” by OpenAI that, among other capabilities, can give amazingly natural responses to questions across a wide variety of fields. Growth fund manager Henry Ellenbogen recently described the technology this way in a recent Barron’s article:

“To me, that [Chat GPT] is as impactful as the iPhone’s introduction in 2007. In a few years, generative AI is going to allow companies to reduce head count significantly in areas where people do rote tasks around human conversation and content creation. Although there is going to be a lot of hype around AI, traditional businesses will use it to unlock tremendous cost savings. I can’t wait to call my phone or cable company and talk to the smartest “person” who knows my account perfectly and can deal with all the technicalities of my setup instantly. That’s where we’re going to be in two to four years.”

Barron’s, “The Age of Free Money Is Over. But There Are Still Opportunities, Investing Pros Say.” January 13, 2023.

Whether the use of AI in customer service comes to pass in that time period and so wonderfully for customer satisfaction remains to be seen. Still, there is no denying that artificial intelligence is going to radically affect some aspects of business and, as with many technologies, enterprises with the resources to deploy it at scale will be big beneficiaries. AI may also help solve the worker shortage that we are facing; more on that below.

We share this recent innovation because it is important to remember that issues of concern for the economy and investments are often easy to identify and tend to animate us (it is self-evident that as a species we are inclined to focus on bad news), while positive developments typically take us by surprise. As with the past, the future will have positive surprises; we just don’t know what they will be. So, while we reflect on the dismal year past in financial markets (and it was a doozy) and take heed of the issues that concern us, we’d do well to also consider the opportunities in the present environment and reflect that those expected difficulties are going to be accompanied by some number of positive developments that we can only guess at. Indeed, we do just that later in this letter.

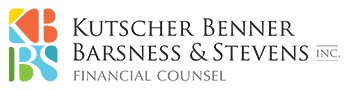

2022 in Historical Perspective. To illustrate just how bad 2022 was in financial markets, consider the chart below. Note how, typically, a down year in stocks (a downward green bar) is partly offset by positive returns in bonds (shown in gray). Not so in 2022. At the far right, it can be seen that both stocks and bonds were strongly down, compounding the downward pressure on mixed portfolios.

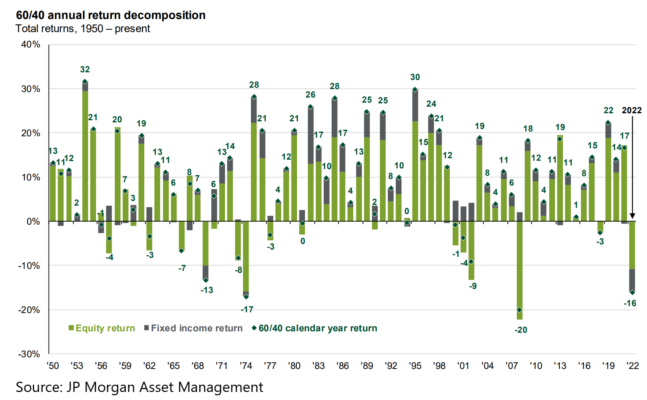

The source of the pain in financial markets was the breakneck pace of interest rate hikes instituted by the Federal Reserve beginning in March that went beyond the historical record as shown in the chart below. Note the steep upward path of the blue line representing the current tightening cycle versus the path of rates in all the cycles since 1958 shown in gray. The Fed’s blistering pace this time, hikes of 0.75% at each meeting, has slowed to 0.50% in December, and market expectations have coalesced around normal 0.25% hikes going forward. The greater debates now are how high the Federal Reserve will ultimately bring its Federal Funds target rate and how long it will hold rates high before easing.

All of this matters, as we explain further below, because the level of interest rates, especially inter-bank borrowing rates that the Fed controls and “risk free” rates like the yield on US Treasury bonds, is one of the most important factors in pricing all investment assets. But before we turn to that discussion, we summarize the tug-of-war between rate hikes and inflation, and we explore some factors that may have longer-term consequences for the economy, corporate earnings, and asset prices. We explored some of these trends in our last pre-Covid letter (January 2020) and they remain relevant in the context of the present battle with inflation.

We know that this type of discussion can be complex and even tedious, but we think it can help frame expectations for investment returns, so is a worthy endeavor for us in our work to help you understand what to expect for your portfolio.

To summarize in advance, while stock prices are down significantly from late 2021, which improves our expectations for returns moving forward over some multi-year measurement period, we would not be surprised if stock prices remain subdued if inflation and/or Fed tightening remain more persistent than the market is projecting. There are both short-term and long-term elements to the inflation phenomenon. If at least some of these risks materialize, it could mean that the coming several years provide better opportunities for bonds and income than stocks and growth when compared to the period since the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”), during which the Fed’s low interest rate policy and asset purchases kept yields low and asset prices (stocks, housing and bonds) high. We address these and other opportunities toward the close of this letter, after explaining the economic backdrop.

Inflation and Wages. The Fed’s stated goal is to bring inflation back down to 2%. The market is currently projecting that the Fed will succeed in this goal earlier than the Fed’s projections, meaning that market interest rates reflect a belief that the Fed will cease rate hikes sooner and eventually cut rates earlier than the Fed itself is projecting. The accuracy of that collective judgment will have consequences for asset prices as we move to the eventual end of the hiking cycle.

In part, the market may be exhibiting wishful thinking (since market participants prefer lower rates and higher values), or greater optimism about the Fed’s ability to battle with inflation and achieve an economic “soft landing” (more on that below) or a misreading of the Fed and especially Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s willingness to defend the Fed’s (and his) reputation from responsibility for embedded inflation. On that last point, former Fed Governor Randal Quarles tells a story of working late at the Fed and meeting the night watchman; even the watchman knew that Fed Chair Arthur Burns was held responsible for the runaway inflation of the 1970s. From Powell’s statements one can infer that he intends to avoid becoming the next Arthur Burns, even at the cost of a recession.

(We allow this reference to Burns as an illustration of Powell’s resolve, not because we think the present situation is a repeat of the 1970s (a hot-button and unnecessary judgment). Each era has its own challenges and inevitably we will navigate our way through this one somewhat differently than the past. Looking for repeats in history can be simplistic and can obscure the differences in conditions then and now, which are substantial. Rather, in this letter we attempt to focus on the longer-term trends unique to the present environment that have implications for inflation and interest rates, and thus returns on financial assets.)

Regardless of whether the market is right that the Fed could cease hikes earlier and still beat inflation, it’s useful to reflect that both the market and the Fed underestimated inflation as it rose to its peak, and the market underestimated the Fed’s vigor in raising rates. Having said that, we acknowledge the difficulty of the Fed’s task and its apparent tendency to message hawkishness as a means of keeping Wall Street in check lest market enthusiasm blunt the Fed’s effectiveness. Nevertheless, it’s prudent to have some skepticism about whether asset prices reflect the extent of economic weakness that the Fed may eventually cause either by putting rates higher or maintaining higher rates for longer than the market projects.

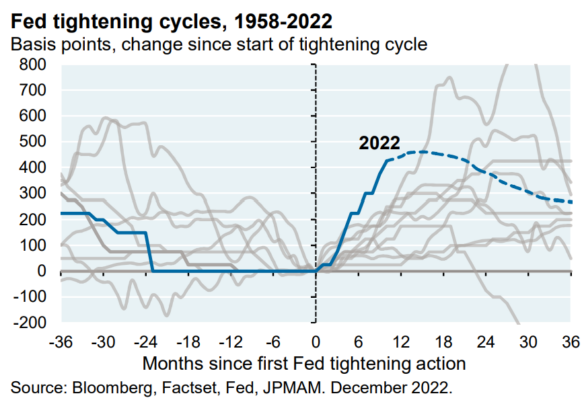

It is also useful to consider the historical perspective of how long it takes inflation to normalize. Looking at the experience of high inflation in developed countries since the 1970s, inflation tends to remain elevated, if in decline, for several years following a spike. Even if the US outperforms the historical record, it still bespeaks caution about expecting inflation to settle quickly back at its pre-pandemic 2% level, although we may get some very low (even potentially negative) episodic readings on inflation within the next 12 months as current prices are measured against spikes in the recent past.

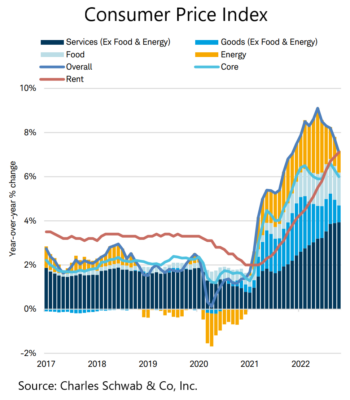

Inflation is clearly coming down, partly as a result of measurement against the high year-ago level and partly as supply constraints that stemmed from Covid disruptions and the goods spending binge from 2020 to 2021 finally resolve. The composition of inflation as captured by the Consumer Price Index is shown in the chart below. Note the baseline foundation of services inflation near 2% for the three years before the Covid pandemic and the virtual absence of goods inflation. If we looked at a longer chart, we’d see that pattern stretching back to the 1990s. This illustrates the difficulty of the Fed achieving its stated goal of inflation dropping to 2% beyond episodic low readings against year-old price spikes. Based on the last few decades of experience, we would need goods inflation at zero and services inflation down significantly. As explained further below, there are reasons to believe that economic conditions that formerly allowed essentially zero goods inflation to persist for years are abating or reversing course.

Wage growth gets a lot of attention from the Fed as a factor in inflation, and wage growth has been very strong since the economic reopening begun in late 2020 as shown in the Atlanta Fed Wage Tracker Index below. It is intuitive that if necessities cost more (e.g., haircuts, insurance, health care, not to mention volatile items like food and fuel), then workers will seek higher wages. Likewise, if wages are rising, companies will try to raise prices if they can in order to maintain their profit margins. In economics, this dynamic is known as the “wage-price spiral,” and the Fed is focused on preventing it from taking hold.

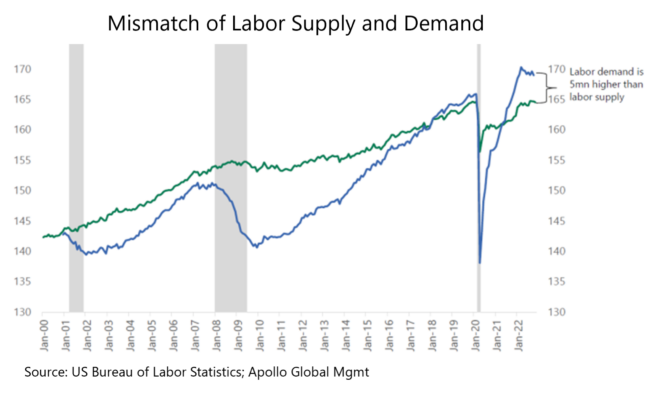

An Economy Short of Workers. Because the US economy is short about 5 million workers, bringing wage growth down is more of a challenge in the current cycle compared to the past. Firms are more apt to hold onto workers and pay them better if they are difficult to hire or replace. Thus, as the Fed hikes rates, there is less effect on company staffing levels than in past cycles. Observe that the Fed has been hiking rates for 10 months, yet the unemployment rate has actually moved down and layoffs (outside the technology sector) have barely budged, compared to, say, the housing market, where higher interest rates directly translate to cooling prices and construction. Consequently, the Fed may need to hike higher or hold rates up longer than in the past, which calls for a measure of patience in our expectations for stock market recovery.

The shortage of workers became quite noticeable when the economy reopened following the Covid-related shutdown. Prime age workers (those 25-59) have returned to the labor force, but near retirement age and older workers (over 59) have not returned as before. Sickness, fear of sickness and lifestyle reevaluation are all reported causes. As well, immigration was reduced during the pandemic. Put it together, and there is a shortage of workers that can’t quickly be rectified.

In financial markets there are dual perils in extrapolating current trends into the future and, by contrast, believing that some changed circumstance means “everything is different.” Thus, we need to be humble and choose with care those phenomena to highlight as truly significant. When considering the economic landscape, the availability of labor now versus prior decades stands out as a significant change likely to persist, putting upward pressure on wages in a manner we are not used to seeing. Immigration could solve the problem, but requires an overhaul of our system to encourage and admit workers with needed skills, and that overhaul has been politically impossible since at least the George W. Bush administration. Meanwhile, the fertility rate in the US has dropped from 2.1 live births per woman (a level consistent with a stable population) before the Global Financial Crisis to 1.6 today. This recent decline in fertility compounds the effect of a multi-decade trend of diminishing workforce participation among “prime age” (25-59) non-college-educated men.

Trade Flow Realignment and Energy Transition. There are two other significant trends that are putting upward pressure on prices. A realignment of globalization-era trade flows is under way that began with the US reconsidering its relationship with China (starting in the Trump administration) and gathered pace in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

China was admitted to the WTO partly as a reward for economic opening that started in the early 1990s during the era of Deng Xiaoping and partly in the hope that China would continue to evolve towards an ever more positive member of a Western-led rules-based international system. That hope is now largely gone and replaced by a grudging acceptance of strategic economic and military competition. We are seeing companies reevaluate China as a base of manufacturing for Western goods, with SE Asia and India as the beneficiaries of these changed flows. The Biden administration has moved to cut China off from the most cutting-edge tools in semiconductor manufacturing and obtained passage of the CHIPS Act to jump-start renewal of semiconductor manufacturing in the US. Companies are returning some parts of their supply chains to the US to improve resiliency at the cost of efficiency. All of this costs money, and it is worthwhile to reflect that China’s development since Deng contributed enormously to the global labor force, dampening US wages while enhancing corporate profits and holding down the price of imported goods available to consumers in the US.

The leading Western countries placed economic sanctions on Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine, notably limitations on the volume and price of petroleum products. Putin responded with reduced flows of oil and natural gas. Consequently, Europe can no longer rely on Russia for cheap energy and is racing to backfill with new infrastructure to receive liquified natural gas imported from the US and Middle East, as well as accelerating an already significant building of renewable energy generation. Likewise, the energy transition is gathering pace in the United States, as is evident from the energy subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Putting this new infrastructure in place requires enormous resources, especially of minerals and the traditional energy (e.g., oil) needed to extract them from the earth.

So, summing up, the current environment: inflation is cooling, but the Fed seems to want more evidence than the market thinks it should need, and in the longer term the composition of labor force, the cost of new infrastructure and realignment of trade flows may continue to exert upward pressure on prices and hence interest rates for some number of years.

Investment Opportunities. Notwithstanding this sober assessment, there are significant reasons for optimism, in part because of the repricing of assets over the past year and in part due to what an environment of higher interest rates means for investors looking for returns on their money.

- With US stocks down about 18% in 2022, stocks are more reasonably priced than in much of the post-GFC period and reflect a largely neutral level compared to projected corporate earnings (the so-called “P/E level”). (Click here to view chart.) That bodes better for future returns than where stocks sat in late 2021, when we opined that returns had been significantly borrowed (brought forward) from the future. We’re exploring opportunities to streamline stock allocations, reduce portfolio costs and improve income from stocks.

- Yields on a variety of bonds are finally available at levels near with what was obtainable before the introduction of the “zero interest-rate policy” (ZIRP) following the Global Financial Crisis. It was ZIRP that created the TINA (“there is no alternative”) mentality of investors moving toward riskier assets, the most extreme of which were loss-making small-cap growth companies, “meme” stocks (like GameStop) and cryptocurrencies. With yields being a reasonable proxy for the expected long-term return from bonds, the relative attractiveness of bonds versus stocks has improved. (Click here to view chart.)

- Still, the reduction in new issues of bonds means that some companies will have trouble eventually rolling over their debts. (Click here to view chart.) We expect this could be reflected in markets discounting high-yield and corporate loans more generally, which would dampen client investments in those areas. Yet, for managers skilled at credit evaluation, especially in corporate restructurings, the opportunity to profit is improved, and may get better still as higher interest rates persist and bond prices decline.

- The US stock market outperformed the rest of the world from the GFC through perhaps 2022, the longest streak in a cycle that has changed ascendancy periodically over many decades. Last year, developed international markets outperformed the US even in US dollar terms and the emerging markets weren’t far behind despite the rising US dollar on the tide of Fed rate hikes. (Click here to view chart.) Given the more attractive pricing of foreign markets, and the potential for downward pressure on the dollar (it’s already in decline compared to last year’s high point), the possibility for enhanced returns to globally allocated portfolios is improved.

- Growth stocks were hit especially hard last year as interest rates rose, making distant profit expectations less valuable. The growth segment of the stock market was augmented significantly over the past couple of years with IPOs of loss-making, but growing and interesting companies. Sorting out those companies that will never be profitable from those that are either on real trends to profitability or can adapt their business models creates an opportunity for skilled growth managers similar to the sorting process the followed the dot-com bust, albeit among companies with, generally speaking, far more tangible prospects and durable franchises than we observed back then. (We would comment that the cryptocurrency/meme-stock landscape of today is the better analog of the dot-com busts of yesteryear.) (Click here to view chart.)

In addition to these opportunities, there are further reasons for optimism:

- China has abandoned its “Zero Covid” policy, is reopening its economy, has put support under its faltering housing market, and has signaled an end to surprising government moves against major technology companies. While the technology schism we first wrote about a few years back is clearly underway, we expect development of China’s economy to continue with opportunities for investment in areas oriented toward domestic technology development, rather than trade with the rest of the world. That said, China’s strategic competition with the West makes the country an interesting and challenging investment case. We will write more about it in future letters, but we’ll note that Russia’s economy is controlled by a cartel closely connected with a single leader, Putin, who has presided over nearly all of Russia’s post-Soviet existence. By contrast, China has a dynamic private sector characterized by entrepreneurship, innovation, and significant access to venture capital. The scale of this dynamism and of the broad Chinese administrative class that has developed over several decades means that robust private ownership is very likely to continue in China even as Xi Jinping has entrenched himself in leadership for life and seeks greater control over private companies. We might find additional hope in China’s relatively measured engagement with Russia since the invasion of Ukraine, perhaps evidencing a preference for economic development when it comes in direct conflict with autocratic impulses.

- The war in Ukraine will end at some point, perhaps in a stalemated line of control, such as exists on the Korean peninsula. In any event, the rebuilding of Ukraine’s economy and the reopening of certain trade flows would be a salutary lift. It is hard to imagine Europe going back to purchasing Russian energy in former volumes, but there are a variety of other trade flows (especially of grain) that have been disrupted as well, and restoring those would relieve pressure on the goods and countries involved, providing tailwinds for returns from the foreign stock side of portfolios in ways not seen for more than a decade

Beyond being fiduciaries in respect of client portfolios, we are likewise focused on counseling clients through segues in their finances brought on by life’s events, their cash flows, taxation and sustainability of their retirement withdrawals and much more. We look forward to seeing you soon, and encourage your calls and emails with questions on this newsletter or any other financial matter.

Thank you for your confidence in us, and for the friendship we enjoy in our conversations and visits with you. Best wishes to you and your families in 2023.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE INFORMATION

You should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this newsletter serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from KBBS. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to their individual situation, they are encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of their choosing. KBBS is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm.