Many essayists have employed the above excerpt from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, a follow up story to Alice in Wonderland. It is common enough that using it now risks the charge of cliché. But seldom has the misuse of a word—in this case, “reciprocal” in President Trump’s April 2nd tariff announcement—been so widely broadcast and with such serious consequences. Lewis’s brilliantly insightful nonsense is undoubtedly apt in this instance. Note here also—especially in view of the constitutional doubtfulness of Trump’s authority for the announcement—the applicability of Humpty Dumpty’s retort: The question, ultimately, is about who is master of the issue.

As virtually everyone knows, Trump’s Wednesday afternoon announcement took the financial markets by surprise, leading to a markdown in US stocks by about 10% by week’s end (on top of 4% declines in US stocks for the quarter just ended March 31). It isn’t as if economics departments at major investment banks hadn’t forecasted a significant increase in tariffs. Goldman Sachs is a good example in raising their expectations from a baseline 10% increase as of early March (already far in excess of the about 2% difference in trade-weighted reciprocal rates) to a 15% increase the week before Trump’s announcement.

Trump’s rates came in at 18% on average, but about 13% trade-weighted after exemptions (such as no tariff on semiconductors) . This includes a base tariff rate of 10% on even countries with whom the US has a trade surplus. (The figures may rise some as we go to print with the announcement of “sectoral” tariffs on particular product categories.) Rather, the shock was because of some of the headline rates (e.g., 44% on Sri Lanka), tariff rates applied to the tiniest nations (50% on Lesotho, really?) and the unorthodox use of a country’s trade surplus with the US (measured as a percentage of the country’s exports to the US) as a proxy for total tariff and non-tariff barriers.

One may be tempted to think that if we’ve (pardon the mixed metaphor) passed through the looking glass, all bets are off—that expectations of rewards from investing drawn from history are no longer useful. To the contrary, we see this extreme event in the context of a long history of political-policy events that occur from time to time and precipitate a change of geographic leadership among financial markets or other significant change in investment themes :

- Following a Camp David weekend with advisors, Nixon’s exit from the gold standard, effectively ending the post-WWII Bretton Woods agreement among countries to manage fixed exchange rates among currencies, and imposing a 10% tariff and wage and price controls;

- Fed Chair Paul Volker’s “Saturday night massacre,” where he drastically hiked interest rates and instituted money supply control at an unscheduled weekend meeting and called in financial reporters for an immediate press conference;

- The Plaza Accord of 1985 where major country finance ministers agreed to lower the value of the US dollar;

- The maturation of the European Economic Community into the European Union, including directly elected representatives, the enforcement of a greater number of regulatory norms from Brussels and eventually a common currency;

- China’s ascension to the World Trade Organization; and

- The United Kingdom’s vote to exit the European Union (“Brexit”).

This list doesn’t even address geopolitical events (e.g., wars) or the now several Federal Reserve policy responses to emergent situations such as the failure of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management in 19 98, the mortgage market meltdown of 2007-08 or the economic shutdown during Covid.

In other words, change is constant in financial markets, but seeing it can sometimes require backing up quite a distance. Before we do that, let’s review market performance for the quarter just ended, which will help illustrate the point about the cycle perhaps turning and provide some comfort in the diverse performance among asset classes.

Tariffs as a Marker of a Changed Cycle. As we noted in our early March letter, the positive returns of bonds and foreign stocks during the first quarter helped offset the negative returns from US stocks as the adverse effect of Trump’s policies started to be priced into the US market, which had grown fragile on spectacular returns to a handful of mega tech stocks. With Trump’s announcement of reciprocal tariffs, and the other elements of his administration that represent abrupt change from the post-WWII economic and security arrangements, we may be passing through a juncture that represents the turn from the long leadership of US markets toward foreign markets, which are both more reasonably priced and have been jolted, to some degree, into more growth as a matter of necessity in dealing with changed US policy.

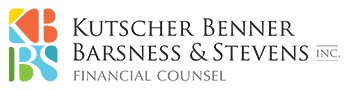

The persistent underperformance of foreign stocks relative to US stocks since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-09 has been a source of irritation to owners of institutional and globally diversified portfolios for a long time now. Not only has the foreign stock element seemed of less utility, but the performance drag relative to benchmarks has grown over time as US stocks became a larger and larger share of global stock market capitalization as shown below. The alternative—to rebalance to more US stocks as they go up—runs counter to the most fundamental imperative to buy low.

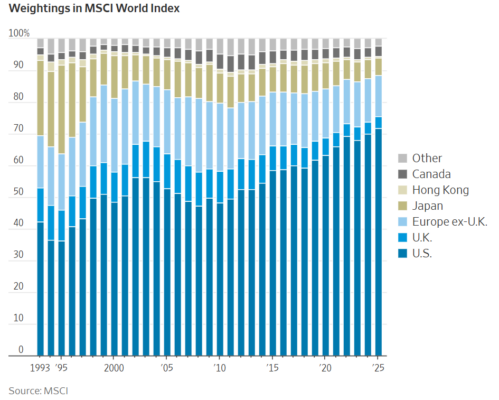

A portion of the US’s outperformance is attributable to inflows of foreign capital to our stock market. This has been a fundamental feature of trade and capital flows for many decades: As a society, the US does not save a sufficient share of our income to fund all of the investment that our economy needs. Foreign companies and investors have been attracted to the returns from investing in US operations and US capital markets (both stocks and bonds) and have been well supplied with dollars to do so with as a consequence of our substantial trade deficit. This is the symbiotic relationship that Trump wishes to upset by using tariffs to drive down the trade deficit. If that happens—and it won’t be known for years—there should be fewer dollars coming from abroad to drive up the value of US stocks and bonds (and keep bond yields lower).

As it is, foreign ownership of US assets is at historic highs (as shown above), leaving much room for foreign investors to pull back from US markets. The opportunity in home-country markets may be more evident to them, they may judge the US as having taken a wrong turn, or indeed we would not be surprised at some pullback as a matter of umbrage at Trump’s treatment of many countries.

Tariff Consequences More Generally. Thus, given the scale of the tariffs, the pattern of capital flows that has dominated financial markets for several decades is likely to change in some respect; that is the biggest effect. The pullback of portfolio investment from abroad could begin, at least in a small way, at any time, while increased corporate investments from abroad, which are much more slow-moving supply chain decisions, remain uncertain despite Trump’s announcements that this or that company is investing in some substantial new project. We find it notable that the dollar has declined in recent months despite textbook expectation that tariffs should support the currency of the country imposing them. That said, for most of last Thursday and Friday while equity markets sold off, the dollar rallied alongside US Treasuries, indicating some persistence in foreigners purchasing Treasuries during times of stress.

More immediately, the imposition of the tariffs is a stagflationary shock to the US economy (i.e., diminishes growth and raises inflation). The tariff is a tax, which may generate $600 billion or more annually and thus represents a withdrawal of money and stimulus from households and businesses. Tariffs also raise prices (that’s the point), at least on imports, except to the extent the tax is absorbed by the exporter or the importer. Domestic competitors therefore have room to raise their own prices and many need to in any event due to the use of foreign-sourced materials. (Note to readers that the tariff rate doesn’t push up the price of goods at retail by the same percentage as the tariff, necessarily. The tariff applies only to consumer goods or materials when they enter the port. The final cost of goods includes all of the effort of distribution and markup for the seller as well, and the exporter or importer may absorb some of the tariff cost.)

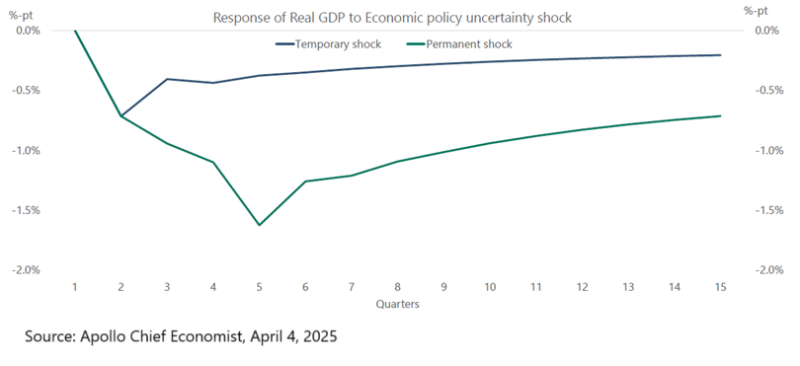

Many economists project the peak effect on US growth and inflation at about 1.5% (that level of drop in GDP and increase in core prices). That may or may not be enough to push the economy into recession given its starting growth rate near 2%. As shown in the chart below from Apollo’s chief economist, the peak effect (or nadir, in the case of GDP) is projected to come five quarters from now, mid-2026, assuming that the tariffs aren’t lifted soon.

Future Developments. Thus, it may take some time for the results of the tariffs to be fully priced into stocks. On the other hand, President Trump may strike tariff reduction deals with particular countries or may find it expedient to radically adjust his plan. Witness his on-again, off-again approach with certain tariffs on Mexico and Canada.

Having said that, and this may be of more interest to Treasury or White House leadership than Trump himself, but there is a political calculus in keeping tariffs in place in service of the administration’s goal to reduce the deficit: tariffs are a rare tax that everyone pays, rich, poor or middle class. Because there’s no tariff on saving, the tax falls hardest on lower income households. Thus far, the tariff has not come from Congressional action, so the political work of justifying raising taxes on the poor and middle class wasn’t done. Rather, the tariffs have been imposed by the President and predicated on preserving and expanding jobs for “working people.” Thus, despite early discussions in Congress about reforming the President’s tariff authority, one must seriously discount the likelihood of these efforts bearing fruit since they would require either Trump’s signature on the bill or a two-thirds vote to override his veto.

Then there is the possibility of courts blocking Trump’s tariff actions. Article 1 of the US Constitution gives Congress, not the Executive Branch, the authority to lay taxes, including tariffs . As with many things, Congress has delegated its duties in some respects on tariffs to the President, both now and for more than 100 years. That said, Trump’s reciprocal tariff announcement is predicated on his declaring the trade deficit to be a national emergency under the International Economic Emergency Powers Act. That statute is silent on tariffs and has most frequently been used to sanction terrorists and other bad actors. The “major questions doctrine”, which was fatal to the Biden Administration’s attempt at wide-scale student loan forgiveness and workplace vaccine mandates, is almost certain to be used by plaintiffs to argue that the statute should not be read so broadly as to permit the president to wield tariffs as a solution to a decades old economic condition (the trade deficit) that persists with much of the world, therefore being neither emergent nor unusual (the predicates for action under the statute) And if the statute is so broad, it is arguably an impermissible delegation of Congress’s authority under Section 1 of the Constitution. Already, there is a case pending in federal court by a company challenging the tariffs on Canada and Mexico and at least one well-funded libertarian group is said to be looking for a lead plaintiff for a case against the reciprocal tariffs. Appeals of this litigation could be before the Supreme Court within a few months.

Staying the Course. In any event, we are monitoring changes in financial markets and will be in touch as and when we believe a trade across asset classes is warranted. As described above, it may take a significant space of time for an opportunity to ripen sufficiently to support a trade, particularly to develop confidence around the purchase side of that trade. Or, the issue might disappear quickly if Trump reacts to stock market declines. Thus far, he has voiced his insistence, and tariffs are the one policy area around which Trump has always had very strong views.

As aggregations of human behavior, markets do tend to eventually swing too far. One thing we thus far don’t expect from the tariffs is significant stress on the banking system of the scale we experienced with the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”), which makes the outcome here unlikely to approach the scale of stress and asset price decline experienced then. That crisis was set off by the popping of a bubble in an asset class (home mortgages) widely owned by banks. There’s no such troubled asset present on bank balance sheets in the current instance. Rather, as the economy weakens, stress will be felt by firms and households and some loans held by banks will be affected. That said, corporations and household borrowers overall are in much better shape than they were during the GFC.

Consequently, in the meantime we encourage clients to remain committed to their investment policies, and to look first to core bonds, which have held up well, if they find current reserves in cash and money markets insufficient to meet needs over the next 12 months. Maintaining discipline, diversification and a long-term focus are critical in periods of rising uncertainty. Note, too, that a prevailing sentiment is that investors should be reallocating over-concentrations in US stock to foreign stock and other asset classes, which our clients’ allocations have included for some time, preempting the need to make a reactive shift when a rotation in market leadership from the US was catalyzed, as may be occurring now .

We hope that this summary of this important topic was useful. We look forward to hearing from you with any questions and endeavor to be responsive to your concerns.