Most of us, thankfully, only know what a bank run looks like from movies and television, most famously from the film It’s a Wonderful Life, a holiday staple of broadcast television in the past. George Bailey (played by Jimmy Stewart), desperate as a young man to leave his hometown of Bedford Falls, is waylaid in his quest a third time when he and new bride Mary Hatch (played by Donna Reed), in a taxi on their way to start their honeymoon, witness a line of customers standing in the rain outside the town’s bank. George looks across the street to the Bailey Building & Loan, his family’s business, where customers are also waiting in the rain before drawn gates. There begins the best scene in movies to explain how banks work.

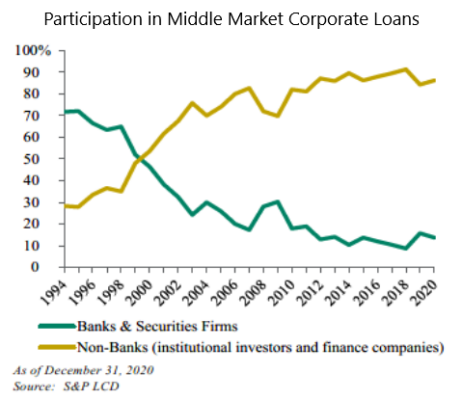

We mention this famous scene because the swift collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and the smaller tremors of the Signature Bank and Credit Suisse failures, collectively, were the big event of the first calendar quarter, a period that otherwise was favorable for investors and helped to reduce the decline evident in trailing 12 month returns.

In light of SVB’s failure, regulation will need adjusting to address the speed at which runs can occur given the rapid spread of information (and disinformation) in the age of social media and the ability of depositors to move account balances with a tap of their phone. No more standing in line to get one’s money. In the space of three days, SVB went from the leading bank for venture capitalists and their startup portfolio companies to a failed institution.

But aside from updating bank regulation—which is drawing a lot of coverage in the mainstream press—it is useful to consider what broader consequences the failure of SVB may hold for the economy and investment opportunities, and most particularly for private lending. That is an investment area we have increasingly been recommending as the investment climate is supportive and as funds appropriate for high net worth investors have become available.

For this exploration, it is useful and hopefully a little entertaining to return to It’s a Wonderful Life and use elements of its famous bank run scene to illustrate how banks work and why private lending makes sense.

Wholesale Funding. Recall that when George enters the Building & Loan, he first confers with assistant manager Uncle Billy in the back office.

GEORGE: All right now, what happened? How did it start?

UNCLE BILLY: How does anything like this ever start? All I know is the bank called our loan.

GEORGE: When?

UNCLE BILLY: About an hour ago. I had to hand over all our cash.

GEORGE: All of it?

UNCLE BILLY: Every cent of it, and it still was less than we owe.

GEORGE: Holy mackerel!

UNCLE BILLY: And then I got scared, George, and closed the doors.

George and Uncle Billy are interrupted by a call from the rich and ruthless Mr. Potter to inquire about the Building & Loan being closed and to say that he has taken control of “the bank,” which will reopen in a week, and that he’s willing to purchase Building & Loan deposits for 50 cents on the dollar.

The bank in Bedford Falls is a much bigger institution than the Bailey Building & Loan. Later in the film, the bank’s fancy lobby is on display as Uncle Billy goes to make a Christmas Eve deposit on behalf of the Building & Loan, only to lose the money and set up George’s ultimate test of faith and endurance. The Building & Loan has borrowed from the bank presumably to help finance its operation of making loans to Building & Loan depositors and it presumably must maintain an account at the bank as part of security for the loan. The bank loan is seemingly a “demand loan,” meaning the bank may call it to be repaid at any time, for example when it believes the Building & Loan may be in trouble or, as here, after Potter has taken control of the bank and calls the loan in an attempt to create a run on the Building & Loan and purchase it for a song.

In modern banking, this is called a wholesale funding relationship. It is “wholesale” in the sense that the bank’s loan is much larger than any of the “retail” deposits of Building & Loan customers. “Wholesale funding” is an amorphous label, but it certainly includes deposit accounts above the FDIC’s $250,000 ceiling.

In the case of SVB, only 6% of deposits were insured, a breathtakingly low figure. Even worse, most of the uninsured deposits were controlled by perhaps as few as 40 venture capital and private equity firms whose networks of partners and portfolio companies were in communication and more or less together pulled their deposits. This extreme concentration helps explain why the SVB experience of sudden collapse is unlikely to be repeated with other banks.

Loan Risk and Maturity Mismatch. Returning to the story, George has hung up the phone on Potter and reentered the Building & Loan lobby to face his depositors.

GEORGE: No, but you… you… you’re thinking of this place all wrong. As if I had the money back in a safe. The money’s not here. Your money’s in Joe’s house…(to one of the men)…right next to yours. And in the Kennedy house, and Mrs. Macklin’s house, and a hundred others. Why, you’re lending them the money to build, and then, they’re going to pay it back to you as best they can. Now what are you going to do? Foreclose on them?

TOM: I got two hundred and forty-two dollars in here, and two hundred and forty-two dollars isn’t going to break anybody.

GEORGE: (handing him a slip) Okay, Tom. All right. Here you are. You sign this. You’ll get your money in sixty days.

TOM: Sixty days?

GEORGE: Well, now that’s what you agreed to when you bought your shares.

The obvious difference in timing between the 60 days in which the Building & Loan must return a deposit and the years over which one of its home loans will be repaid is known as a “maturity mismatch.” The business of bank lending is fundamentally predicated on maturity mismatches. It’s what banks do; they borrow short and lend long. Under almost all circumstances, as a society we don’t worry about it too much and FDIC insurance is a big reason why. And in normal times, we usually aren’t too worried anyway about our bank’s loans going bad and putting the FDIC guarantee to the test.

Credit Risk vs. Duration Risk. The loans George described to his depositors all involved “credit risk,” that is the risk that the borrower might run into trouble and be unable to repay the loan on time or in full. But there is a second big category of risk in debt investing and that is “duration risk,” which means the sensitivity of the value of the loan to changes in current interest rates. A duration of one means that for every 1% change in interest rates, the value of the loan is expected to change by 1%. Two means 2% for every 1% change in rates, and so on. Duration is a function of prevailing interest rates, the exact interest rate payable on the bond (known as the “coupon”) and the length of time before the bond is repaid (the “maturity”). The highest duration debt instruments in common use are 30-year US Treasury bonds, which have a fixed coupon, although obscure bond issues of extremely long maturity (and high duration) exist.

As the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates in 2022 from essentially zero, very low coupon bonds began losing value, not because the borrowers couldn’t pay but because the bonds only made sense to buy on the secondary market if the buyer could get them for a lower price to make the fixed coupon create yield identical to more recently issued, higher coupon bonds. That value can be recovered only if interest rates fall again or when the bond is repaid at maturity.

SVB’s loan book was extremely concentrated in longer maturity Treasury bond and mortgage-backed securities. Those securities had little credit risk, but much duration risk and as the Fed hiking cycle progressed SVB had a larger and larger unrealized loss on the securities. As the venture capital funding cycle slowed down last year, SVB’s deposit base shrank and it had to sell some of those bonds, realizing losses that impaired the bank’s capital. SVB immediately tried to raise capital, but this shocked investors and depositors and, in amazing speed, caused the failure of the bank.

Temporary Funding Solutions. To address what’s required in the face of this situation, we must return to the film’s story. George has made progress persuading his depositors not to sell their deposits to Potter, but they plead to him of their needs. It is important to note that many of the Building & Loan depositors also have accounts at the bank and George has pressed them to satisfy their cash needs from the bank when the bank reopens in a week, rather than the Building & Loan.

MRS. THOMPSON: But my husband hasn’t worked in over a year, and I need money.

WOMAN: How am I going to live until the bank opens?

MAN: I got doctor bills to pay.

MAN: I need cash.

MAN: Can’t feed my kids on faith.

(During this scene Mary has come up behind the counter. Suddenly, as the people once more start moving toward the door, she holds up a roll of bills and calls out:)

MARY: How much do you need?

(George jumps over the counter and takes the money from Mary.)

GEORGE: Hey! I got two thousand dollars! Here’s two thousand dollars. This’ll tide us over until the bank reopens.

(to Tom)

All right, Tom, how much do you need?

The Bailey Building & Loan is thus saved from failure by the wit and will of Mary Bailey to sacrifice the couple’s “honeymoon kitty” in the institution’s moment of need. Likewise, with the failure of SVB and Signature Bank, the Federal Reserve and the US Treasury recognized that unrealized losses on bank balance sheets had the potential to create widespread concern among depositors about the safety of their funds. Closing SVB on a Friday, by Sunday evening, the Fed announced not only that uninsured deposits would be guaranteed, but also a new program, the Bank Term Funding Program (the “BTFP”), which would allow member banks to pledge US Treasurys and US agency guaranteed mortgage-backed securities to the Fed for up to one year in exchange for cash on a dollar-for-dollar basis of par value. Up to that point, banks could pledge qualifying bonds and loans in order to seek liquidity at the Fed’s “discount window” and from the Federal Home Loan Banks at a discount to the current market value of the collateral and then for only 90 days.

Consequences for the Economy. In creating the BTFP, the Fed has effectively taken off the table bank insolvency arising from interest rate changes. Banks still must survive losses that may arise from credit risks they have taken. As the economy cools and likely enters a recession following the conclusion of the Fed’s hiking cycle, banks will inevitably sustain write downs from losses on a variety of loans, including consumer debt, corporate loans and commercial real estate mortgages. However, given the relative strength of consumers and businesses, the coming default is not expected to be especially troubling outside of certain real estate loans, such as those secured by older office buildings. That said, we expect, and have already seen data, that small and medium banks are reducing their pace of lending, probably due to the need to tidy up balance sheets and prepare for more restrictive regulation. This moves recession risks forward.

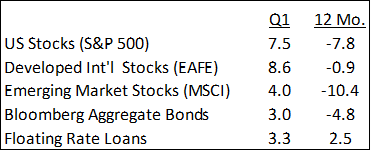

Unique Weakness of SVB Asset Base. As mentioned above, Silicon Valley Bank’s holdings of US Treasuries and agency mortgages created losses at a scale unlike anything present among major US banks. This can be seen in the chart below where banks are listed by their stock trading symbols in the order of their Tier 1 Equity Capital ratios marked in blue. The greater the ratio, the greater the ability of the bank to survive losses by absorbing them in the capital of the bank. Those ratios, as adjusted for losses on securities held by the banks, are marked in brown. JP Morgan Chase, with its “fortress balance sheet,” occupies the far left with the highest ratio. Silicon Valley Bank (ticker SIVB) stands out for its capital being eliminated by losses, despite having one of the highest unadjusted capital ratios.

The Case for Non-Bank Lending. Due to the maturity mismatch of banks and in response to greater regulation to manage that risk, banks have increasingly reduced the share of their balance sheets devoted to various forms of loans and enhanced fee-generating service offerings for their customers, including payment services, wealth management, credit cards and hedging services. For example, anyone who has sought a home mortgage is likely aware that most mortgages are no longer held by banks directly, but after creation are typically packaged into securities and sold into the greater fixed income market where the ultimate holder may be a bank, but is more likely to be a pension fund, mutual fund, insurance company or other form of non-depository institution that is far less likely to be in need of near-term liquidity.

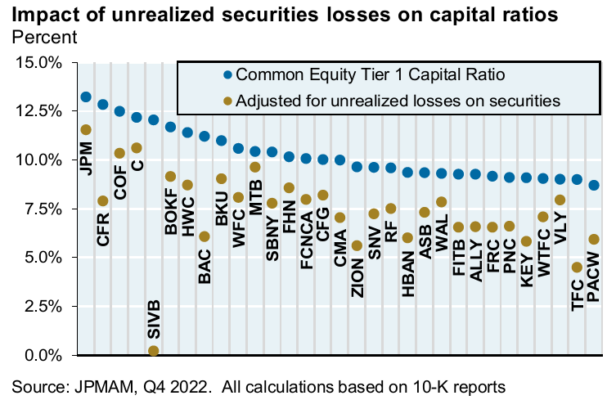

Likewise, banks are less and less likely to be the providers of loans to private companies. Below, courtesy of Oaktree Capital, is a chart showing how private lenders have replaced banks as the principal lenders to “middle market” private companies, those with say $50-$100 million of annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA).

Banks continue to participate in “widely syndicated loans,” which are made to the largest borrowers, some of which are publicly-traded companies, but even there, the banks’ market share is shrinking. As with home mortgages, this change better reflects the needs of banks to protect themselves from depositor withdrawals and the ability of institutional investors to hold these loans to maturity. We also note that private lending pools, which employ leverage typically at 1.0-1.5x their capital, are wildly less levered than the 8-10x of banks (which is observable by dividing 1 by the capital ratio in the chart further above).

We have been looking to assist clients in adding this high-yielding asset class to portfolios, which involves investing in private structures that have limitations on redemption frequency (typically quarterly) and size (5% across a fund). For most individual investors, their investment horizon may be several decades of saving or retirement, creating similarity between their needs and those of institutional investors. Thus, these limitations are reasonable for many investors and even desirable for those wishing to remain invested for a long period.

Other Investment Matters on our Minds. As we move past the stress of banks’ duration troubles, we are now coming upon the deadline for raising the federal debt ceiling. We imagine the posturing and wrangling could easily be worse than the raise in 2011, which means markets are in for some stress. After the raise happens, it will be interesting to see what yield investors demand for new US Treasury obligations. There’s the potential for an upward movement in response to the perception of greater risk, which may challenge the value of other investment assets. And the eventual issuance of new Treasury obligations will reverse the fiscal stimulus that the economy has received since the Treasury started running down its cash balance earlier this year.

We are looking at ways of increasing the yield from the stock side of client portfolios and also ways of reducing investment-related fees, especially in light of the desire for unique assets like private lending that come at higher cost. Look for more from us on that in coming months.

Please reach out to us if you have interest or concerns about any of the above. In the meantime, we continue working on your financial planning, including efforts to make our reporting to you more reader-friendly and, to the extent possible, available in digital form. More on that later this year.

Until we speak next, be well and enjoy the balance of spring.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE INFORMATION

You should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this newsletter serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from KBBS. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to their individual situation, they are encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of their choosing. KBBS is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm.