The close of 2023 finds us in mind of two overlapping trends: one short-term and recently driving financial markets to a handsome rally at year’s end, and one long-term that bodes for change and challenges in financial markets as we enter a period with marked differences, certainly from the Covid pandemic and the policy responses, but also from the post-2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) or perhaps further back. We review these trends in some depth and conclude with implications and actions we are taking in client portfolios.

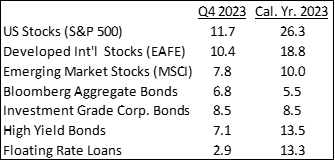

Asset Class Returns for 2023. First, the happy recent trend. In the last couple months of 2023, both stocks and bonds rallied significantly, although stocks have cooled a bit in the opening weeks of 2024. Bond returns ended positive for 2023 and stocks completed a round-trip back to the peak just prior to the start of the Federal Reserve’s hiking cycle in early 2022.

The performance of the S&P was skewed much more heavily than normal by the top 10 stocks, which rose 62% for the year, versus 8% for all the rest. The flip side of that situation is that there is more value in US stocks than the pricing of the largest stocks would lead one to expect.

The cause of the rally has largely been attributed to the Federal Reserve’s seeming satisfaction with the progress of reducing inflation toward its 2% target such that the Fed’s interest rate setting body announced their intention to hold rates steady so long as inflation continues to trend down toward target. Also key has been the Fed’s success thus far in bringing down inflation with interest rate hikes while avoiding a recession. This has been quite an achievement considering the unfavorable historical record. The causes of continued growth despite interest rate hikes are several, including:

- Companies and homeowners mostly having obtained low fixed-rate financing in recent years such that higher rates didn’t affect the interest they pay. In fact, many companies made more money investing their spare cash than they paid in interest on their borrowed funds.

- Cumulative savings of consumers from deferred spending and federal stimulus checks during the Covid pandemic still haven’t been fully depleted, providing a source of continued spending.

- Major federal government spending initiatives, including the Inflation Reduction Act, the CHIPS Act and infrastructure packages, pushed the federal deficit to 8% of GDP in 2023, up from 3.7% in 2022, adding to economic activity.

Likely Market Focus of 2024: Possibility of Recession and Interest Rate Cuts. Whether a recession will still come in the wake of the 2022-2023 rate hikes, and the related issue of the extent and timing of Federal Reserve interest rate cutting, are matters of great debate among economists and, as is apparent to even casual observers of economic predictions, are essentially unknowable. The case for continued growth is buttressed by consumer incomes finally outpacing inflation (after three years of going backwards) and the Fed having room and incentive to cut rates at the sign of real weakness. Those economists more concerned about recession tend to think the pandemic and policy response have stretched the economic cycle but that higher rates will eventually bite consumers and companies, especially when the “excess savings” are fully depleted. They point to subprime auto loans and credit card delinquencies approaching levels of the GFC (2007-2009) as early signs of weakness, as well as unemployment rising about half a percent from its low. At present, financial markets are pricing in interest rate cuts beginning in March and as much as 1.5% for all of 2024, while the Fed itself has published projected cuts only half as deep and starting later. Perhaps the market pricing is an amalgam of bi-modal possibilities: deep cuts corresponding to recession versus essentially status quo if the economy cools without significant unemployment.

Our Larger Consideration: What is the Long-Term Prospect for Interest Rates? We can’t know where the economy is going in the near term or what the Fed will do; it doesn’t know either. (We summarize market interest on the topic only to help clients put economic news in context.) But we take cognizance of the investment landscape and seek to skew investment positioning to capture areas of better value or reduce risk to the extent feasible while staying within the parameters of a client’s investment policy mix of stocks and bonds. This necessarily involves judging whether market pricing reflects realistic probabilities of possible economic outcomes or rather is priced too richly for one outcome due to momentum and sentiment.

While one might think that involves focusing on recent market movements, such as the end-of-year rally and year-opening retreat, instead we are more concerned with the prospects for investment returns of various assets over multiple years, in part by bearing in mind the evolution of longer-term themes and trends. This is analogous to a young car driver learning not to oversteer in order to stay out of the ditches.

Perhaps the paramount consideration now is where “normal” interest rates settle out as the Fed gets through whatever rate cutting it eventually deems necessary to address the economic aftershock of its prior hikes. The foundational interest rate is, of course, the yield that the US Treasury must pay to entice investors to hold its bonds, typically considered to be free of default risk. All other bonds involve varying risks of default (also known as “credit risk”) and thus require higher yields to compensate the holders. Likewise, Treasury yields influence stock prices as investors need greater prospective returns from stocks to compensate them for the volatility of investment return they must endure relative to the contracted interest and principal payments of bonds.

Do we go back to the “zero interest rate” policy of the period from the GFC to 2022? That seems quite unlikely for a host of reasons, including the Fed needing “dry powder” in the form of higher rates available for cutting to stimulate the economy when needed. Having said that, in any particular time of crisis one can be sure that the Federal Reserve would want to cut rates drastically and perhaps again buy bonds for its own balance sheet to drive down yields on longer-term bonds. (We say “want to” rather than “would” to make room for the possibility that high inflation at a time of crisis would constrain the Fed’s ability to act.) Absent such crisis, however, what should one expect as the normal yield on, say, the 10-year US Treasury Note (currently at about 4%)?

The Importance of the US Treasury Market and Government Finances. Our sense is that the current yield near 4% on the 10-year Treasury note certainly seems not too rich (and maybe a bit low) compared to the historical record of what Treasury holders have received in the past.

We also reflect that the supply of Treasury securities coming onto the market is quite large and is likely to remain so for years absent major tax increases or spending cuts. This situation is a function of the following: (1) large federal deficits that have persisted since the GFC and have grown further in size with recent domestic initiatives; (2) Fed sales of Treasurys purchased since the GFC; and (3) the abundance of short-term Treasurys that need to be rolled over. It is hard to overstate the imbalance of the US federal fiscal situation, which is a topic to explore further in subsequent newsletters. For now, suffice it to say the problem has been building for many years and the scale of structural imbalance (about 5% of GDP with no reasonable expectation for decline under current law) is unheard of outside a recession or wartime.

The significance of US Treasury supply can be illustrated by looking at activity in the Treasury market in the second half of 2023. The Treasury shocked the market when on July 31st it announced the large size of its intended funding plans for the third quarter and later backpedaled in the fourth quarter announcement on October 30th. Between those dates, the yield on the 10-year Treasury moved up an entire percent, causing bonds and stocks to fall significantly. The October 30th announcement coincides with the start of the year-end rally in stocks and bonds, which was only enhanced with the Fed’s December announcement that it would probably not be further hiking interest rates this cycle.

Implications for Asset Classes and Portfolio Positioning. This fiscal imbalance and abundance of Treasury supply has significant investment implications that bear on our thoughts about portfolio positioning.

- We should expect foreign investors to be less keen to buy Treasurys since the increasing supply dampens the value of their investment, which would be further harmed if the dollar declines. This diminished incentive to hold US debt coincides with increased weaponization of the dollar over the last several years, including most prominently sanctions on Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine. Already, 20% of all oil traded in 2023 was in non-dollar currencies. We should not expect profits from trade denominated in other than dollars to be recycled into dollar investment assets, something that has buttressed US asset prices for decades.

- To US investors, higher Treasury yields give buoyancy to the yield on corporate and other debt since Treasury yields still represent a kind of floor investment return due to the historical absence of default risk.

- Higher yields on debt are a dampener for stock prices due to the higher interest payments that companies must make on their debt and the competition that bonds represent to stocks as a destination of marginal savings.

Reflecting on these pressures and the relative value of various asset classes that make up client portfolios, we believe portfolios are well prepared for near-term market uncertainty and longer-term prospects.

- If a recession arrives, the core bond funds in client portfolios (e.g., DoubleLine, Guggenheim, TIAA) should help dampen declines from stocks and credit, even if this expectation is less strong given the supply dynamics referenced above. We also like the opportunity for outperformance from the greater dividend-generating stock fund (e.g., JPMorgan Equity Premium) that we have started adding to client portfolios. Finally, in recent client rebalances where the tax cost is manageable, we have also been selling stock funds (e.g., Oakmark Select, Touchstone Sands) with highly concentrated portfolios because as a group they tend to underperform in market retreats.

- If recession is avoided, stocks should do reasonably well, although one may argue that stock prices already reflect this favorable possibility. That said, as mentioned earlier in this piece, there is more opportunity away from the top handful of companies, which tend to be underweighted in non-index funds. See Dodge & Cox, Parnassus, T. Rowe Price and Brown Advisory.

- US Treasury market weakness is a buttress for non-dollar assets, notably foreign stocks, which are trading at greater discounts than normal to US stocks. The median foreign stock outperformed the median US stock in 2023, and we like the substantial allocation that clients have to foreign stocks (e.g., GQG Partners, Impax Int’l Sustainable Economy, Vanguard FTSE Dev. Mkts.) given the opportunity for outperformance measured over the next several years.

- We like the relative attractiveness of much of the non-core, “peripheral bond” areas of structured credit, private credit and high yield (e.g., Osterweis, Oaktree, Ares and Apollo) given the ability to generate yield in the high single digits, near long-term stock returns.

We are happy to address your questions and comments and look forward to working with you here in 2024.

PLEASE SEE IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE INFORMATION AT: KBBSFINANCIAL.COM/NEWSLETTER-DISCLOSURE-INFORMATION/